Alan's musings : home

Free publicity - you can't give it away

an investigation into organizations' capacity

to facilitate and respond to e-communication

..:: a paper by Alan Charlesworth ::..

Introduction

This paper was presented at the Athens Institute for Education and Research

(ATINER) conference on July 5th, 2010 in Athens, Greece.

This paper does not represent 'academic' research with a hypotheses to be proved or disproved. It is simply a record of events surrounding the writing of my book; Internet Marketing: a Practical Approach. To satisfy copyright restrictions, any image used in the book must have permission from the copyright owners to reproduce that image - and as I wanted to use 'screenshots' of various websites, the publishers of those sites had to be contacted. This paper is, therefore, a record of my attempts to contact the relevant person or department to gain that permission.

Abstract

It is accepted that a website's credibility is enhanced by the inclusion of comprehensive contact details. Similarly, the provision of those details is also considered to be a key element in website usability. However, any resulting gain in credibility or usability is a by-product of their primary purpose: ie to facilitate personal contact between outsider and organization.

Taking advantage of a unique situation in order to evaluate organizations' responses, this paper utilizes an enquiry that is both authentic (ie not a fabricated scenario) and which seeks to deliver an un-solicited benefit to the organization.

Deliberately restricting contact to online-only methods, the research evaluates: (a) the ease in which the author could identify and contact an appropriate person or department, (b) if received, the nature of the response, and (c) the outcome of the request and time elapsed between initial contact and outcome. Going beyond simply evaluating the availability of online contact facilities, this research sought to identify a named recipient and assess each organization's internal communications by the nature of its response.

The results show that most organizations' websites rely on a generic contact form or email address and that few include a specific PR or 'press' contact - the targeted recipient. Furthermore, half of the organizations (many of them global brands) failed to even respond to the contact - ironic given the targeted recipients. Smaller companies, however, tended to recognize the opportunity by responding both positively and swiftly.

Research objectives

It is now commonly accepted that an organization's website is an important medium for people to communicate with that organization. This research considered a number of websites for their suitability in initiating contact. More specifically, the objectives were:

- to assess the availability of any contact details on a website

- to assess the availability of appropriate contact details on a website - or is all contact routed through a single point of contact (single email address or online form)

- to assess the quality of response

That the communication was not one that might be considered to be an everyday event tested each organization's ability to cope with non-standard communication.

A review of the relevant literature

Both practice and research has established that having prominent contact details is an essential element in website credibility, with even early writers on effective website design recognised that any lack of contact information was detrimental to the site (Abraham 1996, Landis 1995, Wallace 1995). The key issues are those of customer relations and credibility. Reflecting a marking perspective, Huang et al (2006) suggest that companies should always consider their customers first, therefore the company website must provide links to contactable person(s). Jonathon Hall (2002), in his influential paper for the BBC's training department, listed the 'top 12 sins' of common website faults features 'not having email addresses or online forms' at number two. Vorvoreanu (2006) suggests that even the non-prominent placement of contact details is detrimental to relationships.

With regard to credibility, seminal papers from Fogg (1999) and Stanford University (2002) address the issue. Fogg's 'web credibility grid' emphasizes that websites must have the facilities for users to raise questions and 'receive quick and helpful replies'. The Stanford Web Credibility Research Centre found that number five in its 'ten guidelines on credibility' was 'make it easy to contact you'. More specific to this paper is a comment from the Nielsen Norman Group (2009), stating that; 'if journalists can't find what they're looking for on a website, they might not include that company in their story'. The same research found that when asked for their top-five reasons for visiting a website, journalists identified 'locating a PR contact' as number one.

The debated use of email addresses versus online contact forms centres around the convenience and security offered by forms. Contact forms can be used to collect specific information (McGovern et al 2002) and at the same time collected data can be saved in tab-delimited databases and saved for future use. Forms can also prevent unwanted emails as addresses can be harvested from websites and used by spammers.

However, poorly designed forms can defeat the objective of allowing users to contact the organization quickly and easily. As with much of online marketing, concentration is focussed on the technical development of contact form development rather than what should be included as part of the organization's marketing communications efforts. Focussing on website usability, Nielsen (2005) found that [online] forms tended to be too big and featuring too many unnecessary questions and options. A further issue with forms is that if their design is poor, they are often not accessible to blind and disabled people. The UK's 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, Australia's 2006 Disability Act and the EU's European Disability Strategy (2004-2010) are examples of legislation that would all be breached by websites with such forms.

Not only should contact facilities be easily available, but online customers expect the online retailers to respond promptly to their inquiries, especially e-mail inquiries (Jun et al 2004, Cai and Jun 2003). Although the majority of research into email response is customer-contact orientated, the results are not encouraging. BenchmarkPortal (2005) found that when emailed 51% of small to medium businesses (SMBs) and 41% of large enterprises did not respond at all. Furthermore, when they did respond, 70% of the SMBs and 61% of large enterprises failed to do so within 24 hours. Similar results were returned by Transversal's third annual survey into customer service (2008) with less than half (46%) of routine customer service questions emailed to 100 leading organisations being answered adequately, and the average response time being nearly four days (46 hours). eDigitalResearch and IMRG (2009) found that only 10% of respondents rated retailers' responses to queries as 'excellent'.

Research from Transversal (2008) returned similarly disappointing results (an average response time of 33 hours), but it did find that some companies responded with useful answers within 10 minutes. Poor response to email inquiries is not limited to on-site email addresses. In an informal paper, Jenkins (2007) found that when responding to 41 opt-in emails only six actual human replies were received, three replies were automated messages, six replies bounced and the remaining 26 failed to respond at all. Despite numerous 'business advice' in both off- and online publications encourage a 'prompt' response, that period is not yet determined. Net-etiquette seemingly suggests that 'within 24 hours' as being reasonable, but this fails to take into account working hours and any potential time-zone differences between sender and replier.

The disparity in off- and online response times might suggest that despite organizations recognizing the value of the web as a communications medium, it still plays second fiddle to other forms of contact. The website of UK grocer ASDA, for example, tells visitors that the customer services phone line is available 14 hours a day but it can take a 'couple of days' to answer an email (your.asda.com/section-contact-asda [1/6/2010]).

Primary research approach

For this paper, the research was empirical, it being the recording of the results of a practical exercise. The circumstance was that in the course of writing an academic text-book (Internet Marketing - a Practical Approach) the author contacted 50 organizations seeking permission to feature a 'screenshot' of their website within the text. As the book was Internet-related, it was deemed appropriate that all requests be made only through that medium, accurately replicating a real-life scenario of a customer or stakeholder using the website to contact an organization persevering with the Internet as a medium for that communication.

Although the exact wording was personalized for each organization, the email message was essentially the same for all recipients. That is; permission was being sought for a screenshot of a web page to be used as an exemplar of good practice (none of the in-text examples present the organization, brand or product in a negative light). The details or URL of the required page was included, as was a description of the context in which it was to be used. As not one organization's website listed what might be considered to be the 'right' contact details all messages were prefixed with a suitable message explaining the purpose of the communication, why it was sent to that email address, and a request to forward it on to an appropriate person or department.

All communications used the author's 'work' email address (i.e. on a .ac.uk domain name) to add authenticity [Note that this may have been misguided as research carried out subsequently by the author (Charlesworth, 2010) revealed that Americans in particular are somewhat unaware of the nuances of domain name construction outside the common US suffixes (extensions) of .com, .org, .net and .edu.]. The selection of organizations, brands or products for the illustrations within the book was entirely random. There was no attempt to achieve any kind quota or pre-determined balance in their identification. In many cases the selection was pure chance - an advert being on TV at the time a relevant aspect of a subject was being written, for example. Permissions were requested throughout 2008.

Results & discussion

As this research is based on an actual activity details that might have been recorded in a research project are absent from the results - in particular, the difficulty the author faced in finding a suitable means of contact on the identified websites. Thus, any comments in this regard are both intangible and subjective, but the author can confirm that too many organizations make it difficult to contact them via their website. This situation is compounded when - as in this instance - the contact is more complex than a 'standard' customer enquiry. As the probability of receiving a positive response was important to the author (i.e. a response was required, unlike a research-only exercise where it might only be desired), time was spent in an effort to identify a suitable respondent.

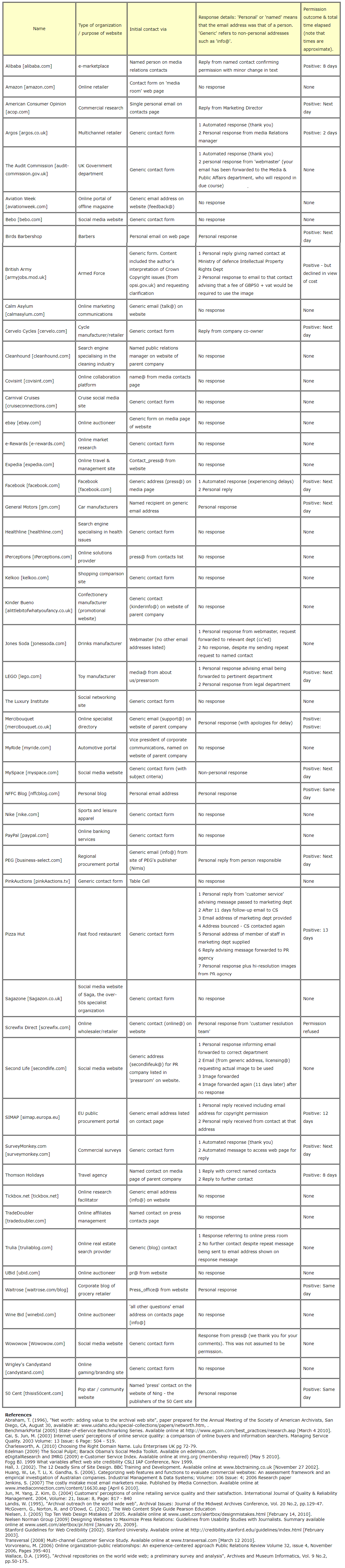

The details shown in table 1 confirm that this was rarely possible, with 34 of the 50 requests (68%) not being made to named recipients. The majority of requests for permission were made via generic online contact forms (23/46%) - the method of communication with dubious usability and (as it transpired) the worst response rate. That such systems are used more for the benefit of the organization than the website user is significant in this exercise where the request was away from the norm. Given that the forms (and generic contact email addresses) are normally designed to meet specific criteria (e.g. customer complaints, delivery tracking) it is reasonable to assume that the response rates to such communications will be significantly better than in this case study.

Perhaps the most disappointing result is that 24 of the 50 (48%) contacted organizations failed to respond in any way to the communication. A further five responded to the initial contact - some with automated replies - but communication subsequently broke down. Positive responses were received from 20 organizations. That 13 (65%) were within 24 hours suggests that those recipients recognized immediately the potential benefits of the request. Only one recipient declined the offer, though the individual who replied was a member of the 'customer resolution team'. The nature of the response suggested [to the author] that the nature of the request had not been appreciated by an inappropriate respondent (note that the email's legal footer prevents the actual message being reproduced in this paper).

Generic contact forms have the worst response rate with 16 of the 23 forms (70%) eliciting no reply. Generic email addresses fared better with a failure-to-respond rate of 50% (8 of 16), but the best response rate (64%) came from named contact email addresses. This would suggest that as far as the initiator of the contact is concerned (the customer/stakeholder) a named email address is most likely to bring forth a response. However, given that the four 'named contacts' that failed to reply were; a PR manager, a VP Corporate Communications and two named individuals on press/media web pages this cannot be considered an absolute.

Although the actual size of each organization is not established categorically, it is the case that some are obviously large or small (e.g. a global brand name or a personal blog). Of the seven organizations that are easily identifiable as 'small', six replied within two days and all agreed to permission being granted, suggesting that with small organizations the message arrives at a responsible person who recognizes the value of the proposition. It is also the case that the websites of smaller organizations tend to include named email addresses.

Conversely, 19 organizations that can be identified as 'large' failed to respond to a generic form enquiry, including the global brand names Amazon, ebay, Expedia, Kelkoo, Kinder Bueno, Nike, PayPal, Saga and Wrigley. For these organizations it can be reasonably assumed that their PR/marketing departments would either recognize the opportunity or politely refuse it - suggesting that the communication from a generic form didn't reach an appropriate person or department. Having made this assumption, however, of the 13 contacts that can be identified as being PR or press professionals seven (54%) did not respond - suggesting shortcomings in these professions. Similarly, of the 35 organizations in e-commerce provision or online trading that may have benefited from the book's readers contacting them with regard to business or employment opportunities 22 (63%) failed to respond.

Table one illustrates details of the author's permission requests and the associated responses.

Practical implications and value to organizations

While it is reasonable to conclude that not appearing in an academic textbook is hardly likely to impact on an organization's turnover, the same might be said of any branding efforts. Similarly, there is a reasonable argument that a genuine customer who wishes to contact the organization is more important than an author seeking re-production permission. However, it is reasonable to expect that in the contemporary business environment organizations should make it easy for any individual to reach any person or department within that organization. The take-away for any marketer from this report would be that it is not that difficult to employ best practice in this respect, but it is easy to get it wrong. Best practice in external communications have been established over the years that new technology has been employed - telephones not ringing more than three times and supermarket customers not being obliged to wait more than a few minutes, for example. But it would appear that Internet-initiated communication has still to be considered in the same way as more traditional methods of conversing with customers and other stakeholders.

This can perhaps be best summed up by a more recent case study: As the author is constantly writing content for one book or another, so seeking permission is an on-going pass-time. It is in seeking permissions for the second edition of his book with Richard Gay (Online Marketing: a Customer-Led Approach) the author came across a report published by Edelman (The Social Pulpit; Barack Obama's Social Media Toolkit, 2009) which addressed Barack Obama's use of social media in his campaign for the US presidency and thought it would make an excellent case study. An email was sent to the report's principal author, Monte Lutz - and a positive reply was received within an hour. This on a Saturday afternoon! What is Edelman's business? Perhaps it's no coincidence that the organization that has best recognized the value of being featured in a text book is one the world's leading public relations firms. And Mr Lutz's job? Senior Vice President, Digital Public Affairs. Now there is an organization that practices what it preaches.

Table 1: Details of the author's permission requests and the associated responses.